Superheroes, evil aliens, trippy plotlines, comic disproportion, a farting planet. The new cartoon series <em>God’s Gang</em> has all the trappings of classic juvenile entertainment…except the fundamental premise.

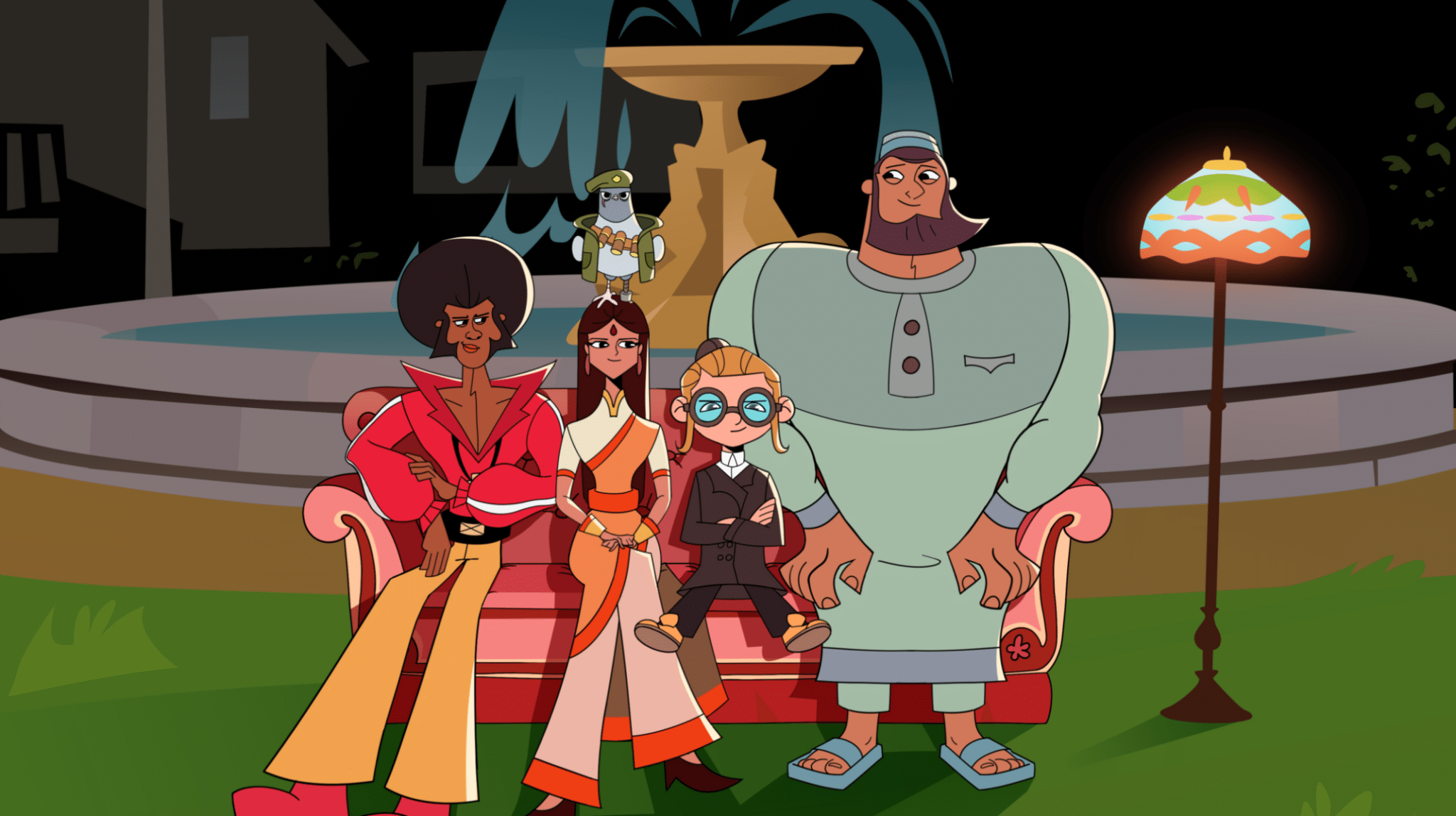

<em>God’s Gang</em> centres on the friendship of a group of superheroes from four major world religions: a Muslim – “Sumoslim”, a Hindu – “Taekwonhindu”, a Jew – “Ninjew”, and a Christian – “ChrisCross”.

Aided by two of God’s sidekicks, a dog called “Ms Dogma” and a pigeon called “Le Dove”, the team drive around in a Scooby-Doo-style van defeating evil through the use of spiritual superpowers inspired by elements of the four religions they represent.

The cartoon’s creator, Nimrod-Avraham May, an Israeli ex-Disney marketing executive, first conceived of the idea of an interfaith superhero group while addressing other Disney execs at a conference in the mid-2000s. Initially well-received, the idea went nowhere until May created his own studio and got to work making the series during Covid lockdown, inspired by his own spiritual search and his commitment to creating a better world for his daughters.

The team behind the cartoon is impressive. The Emmy Award-winning Rob Kutner’s writing fits the prescription for teen cartoons with a flicker of the dry humour and off-the-wall narratives of <em>Rick and Morty</em>. The animation is slick.

Where the show fails fundamentally, however, is in the premise. May describes a process of consulting with a team of individual faith leaders. What’s strikingly apparent though is the lack of understanding of interfaith dialogue as an actual practice.

Attempting to turn the tools of humour and animation towards a meaningful message of interfaith friendship, the cartoon presents the equivalent of a nonreligious person entering an interfaith discussion and – finding it slow, complex, unyielding and often heated – stands on a chair to tell everyone that they just need to love each other. As if that wasn’t the purpose of the dialogue to begin with.

There’s an old Indian parable that’s been widely abused to fit a way of thinking about global religions: several blind men attempt to describe an elephant by touch, but each has a hold of a different part and so they seem to be describing different things.

For one blind person, this thing (God/ the elephant) is long and thick and flexible (the trunk); for another it’s flat and flaps about (the ear); for another it’s thin like a rope (the tail); etc. You might have heard this parable being used to account for the differences in world religions, the conclusion being that all religions are ultimately talking about the same thing from different limited perspectives.

The main issue with this misapplication of the parable is that the person capable of telling this story must have sight where all others are blind: the storyteller alone can see the whole elephant. From this stems the fatal flaw at the heart of <em>God’s Gang</em>.

May assumes an enlightened position. Just like the poet John Godfrey-Saxe, who originally miscomprehended the elephant parable to be about interreligious dialogue, May is the only one who can see what all these religions are disputing, and wants to impart his truth to the blind.

But in doing so, he and his team consistently either misrepresent the religions or simply miss the point of them altogether. An example of this, already raised by some discontented viewers, is the decision to arm the Muslim character with a "falafel bomb".

The ambition of the cartoon is to create an entertaining and light-hearted platform for children to imagine friendship and fellowship existing between diverse communities. This ambition in itself is clearly a good place to begin.

However, the focus of attention is fundamentally misdirected throughout. All the creative energy going into the show seems to be around gimmicky pseudo-spiritual powers and quashing the diabolical plottings of spurious evil characters by often violent means.

Friendship, depicted in any profound sense, is pretty absent. The characters aren’t convincingly friends with each other at all. They are much more like awkward colleagues who’ve been put together on various team-building missions by a manager who wants to promote employee productivity.

Far richer, and far less patronising, food for the teenage imagination would come from shifting the show's focus away from telepathic tricks, falafel bombs, or superficially addressed differences of diet, to the real-life knottiness of friendship in diversity.

Let’s imagine an episode in which the dilemma arising is more complex than beating up aliens. The team encounter genuine culture clashes and have to use their interfaith superpowers to help these communities find a way through while remaining together.

In an interview on <em>YouTube</em>, May claims: “We’re not trying to preach anything”. This feels like a comment dangerously lacking in philosophical maturity and self-awareness. Atheist philosopher John Gray once said the most dangerous self-delusion of the modern age comes primarily from the secular West and those who would claim: “I don’t believe in anything”.

Nevertheless, May does seem genuinely open to criticism and redirection. There are currently only two episodes available online and the feeling is that this is all still in the pilot-stage of production.

I’d encourage any interested reader to leave a <em>YouTube</em> comment with feedback, which seems to be being diligently read and responded to, or to get in touch with the creators directly (<a href="mailto:info@godsgang.com">info@godsgang.com</a>).

The concept behind the show is perhaps not a lost cause and could even, some way down the line, become genuinely fruitful ground for introducing interfaith dialogue to young viewers.

Until then, though, its appeal will ultimately be limited to those who share its creator’s view of the world, that increasingly chosen tick-box on European and North American census forms of “spiritual, but not religious” – a perspective which is notably not represented in the cartoon itself. <br><br><em>Photo: The characters from the animated series 'God's Gang', (L-R) Chriscross, Taekwonhindu, Ninjew and Sumuslim. (Screenshot from <a href="https://www.jta.org/2024/01/26/culture/who-is-behind-gods-gang-a-new-multifaith-animated-show-that-draws-on-jewish-and-other-stereotypes"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">www.jta.org</mark></a>.)</em><br>